The last born in a family of six raised by a single mother, Seabe Ramoruswana admits he was a very naughty little boy.

Unable to shake off this childhood mischief, the Thamaga native’s wayward behavior persisted into his teenage years, eventually landing him in trouble with the law.

Now 36, Ramoruswana has wasted a large chunk of his life behind bars.

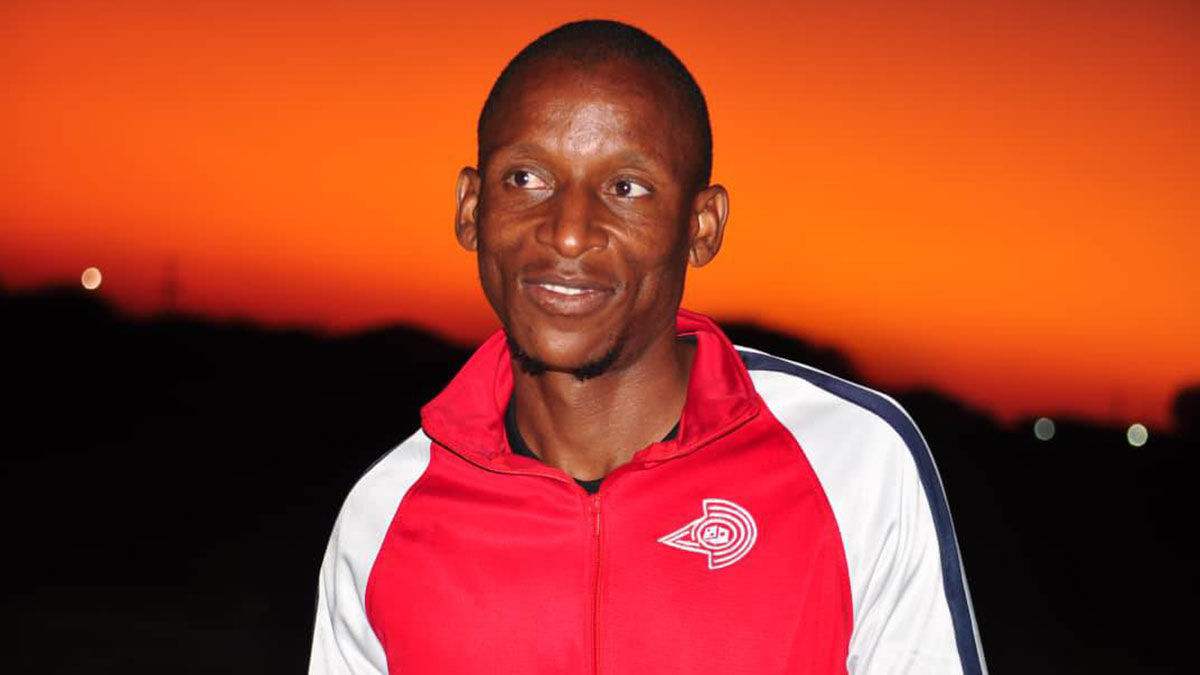

The ex-convict, who has been on the straight and narrow since his release from prison in 2014, gradually rebuilding his life one step at a time, tells The Voice his is a tale of ruin to redemption.

“I started stealing from home from a young age. Whenever my mother or sisters kept a handbag, I snatched some money from it to buy whatever I wanted; that became a habit and I started taking more money. I didn’t have much love in attending school and when I completed my Standard 7 my mother decided that I take transfer to stay with my sister in Lobatse believing that I would get better,” recalls Ramoruswana, ruefully noting the opposite happened.

After dropping out of school, keen to escape his sister, who refused to put up with his antics, the youngster retraced his steps to Thamaga, seeking shelter with his mother.

However, furious that her son had quit school, she sent him packing. He was just 14.

With nowhere to go, Ramoruswana broke into a neighbour’s house, where he stayed for the next four days, confused and angry with the world.

Spotting his distress, a good-hearted Samaritan took the teen in.

Despite this random act of kindness from a complete stranger, feeling betrayed by his family, his juvenile behavior grew steadily worse.

“I started breaking into people’s houses, stabbing people with knives, committing crimes of robbery, mostly targeting Indian nationals. By 2003, at the age of 16, I was sent to Ikago Rehabilitation Centre.”

The stint in young offender’s further fuelled Ramoruswana’s sense of injustice and by the time he was released back into society, he was desperate and dangerous.

In 2006, he was charged and found guilty of robbery, armed robbery and unlawful wounding.

Having turned 18 and now viewed as a man in the eyes of the law, the courts came down hard on Ramoruswana, sentencing him to 19 years imprisonment.

It was later reduced to eight years, with an additional three months extra mural service thrown in.

Reflecting on his incarceration, the ex-convict warns prison is no picnic.

“I could not sleep or eat properly as prisoners are only served with porridge, maize meal, samp and beans with vegetables. In prison there is no large meat as people say; every prisoner eats two pieces only, one small piece is cut into two and that is your portion for the day.

“A prisoner should eat three teaspoons of sugar per day – he is the one to decide if he uses it for tea or soft porridge. You also get a small space to sleep; 30cm is provided and you only sleep on your side. If you’re to serve 10 years you spend all those years sleeping in the same way!”

Aside from the poor diet and difficult sleeping conditions, the threat of violence and sodomy also looms large.

“Hungry prisoners who are not eating well buy food through anal sex from those cooking for them. They don’t use protection and many end up getting sick,” he reveals.

A free man for the last nine years, the reformed Ramoruswana is unrecognizable from the youth who terrorized Thamaga in the early 2000s.

He has put his energy into community development, dividing his time between his role as Chairman of Rehabilitation Centre for Ex-Offenders, a non-profit organisation he founded, and coaching Terror Classic SC, a boys team that plays in the Kweneng Youth Leagues.

“Some of our boys are now in national teams for Under 15 and 20,” he reveals proudly.

“I am much interested in raising a boy child, especially those raised by single parents. I did self introspection whilst in prison and realised children need fathers to guide them. I make a plea to everyone who wants to see changes in reducing of crime to support us. We need some money for transport and food for football tournaments.”

Ramoruswana also encouraged the community to help his organisation support convicts to show the spirit of compassion and love and raise children to prevent crime.

“Let us appreciate and reward ex-convicts when doing good things and avoid discrimination and stigma to inspire them that there is life after prison that they shouldn’t commit other crimes and return back to prison, let’s catch them doing something right,” concludes the man who is living proof that change is possible.